A Brief History of Fishing on the Outer Banks

“The Goodliest Soile Under the Cope of Heaven.”

Despite being a slight string of sandy shoals, there is no doubt that the Outer Banks of North Carolina have been loved by all who visit and are called “home” to thousands year-round. In addition to the natural beauty of surf, sand, and sun, the Outer Banks is steeped in splendid history dating back to Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1585 settlement of what is known today as “The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island,” in a race to conquer New World territory fueled by Spain’s presence in Florida. The history of the Outer Banks commercial fishing industry closely corresponds to the development of the state’s agriculture, beginning as pure sustainment for early settlers and developing into a booming commercial enterprise. Large fisheries in the Albemarle Sound were created during the late colonial and antebellum periods, and through the development and increase of transportation and availability of ice in the 1900s, independent watermen began to emerge, as did the development of fresh fish and shellfish markets which laid the foundation for the modern coastal fishing industry on the Outer Banks.

Colonial Period

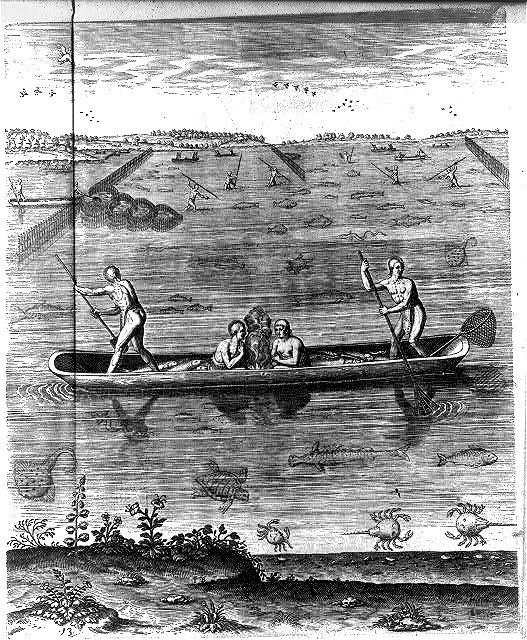

What has quickly become a bustling tourist destination, was at one time virginal land where Algonquian Native Americans had thrived, employing the barrier islands’ bounteous waters and fertile grounds for food gathering and sustenance. There was no scarcity of fish, and the Algonquians’ sustainment methods were rich, varied, and proved to be fascinating to the early English settlers. Algonquian fishing techniques utilized weirs, an underwater netting originally constructed with reeds, which confined and gathered various species of fish such as trout, mullet, and flounder. Sharpened poles and spears were also in their repertoire of equipment and proved to be incredibly effective as they hurled them off their boats in the open waters or wading in the shallows.

As the settlers arrived, they began navigating and using the sounds, inlets, and ocean which created a community of expert boaters and established maritime trading off the Carolina coast. The fish were plentiful and proved to be good meat which was essential to Native Americans and colonists alike. North Carolina’s first surveyor-general, John Lawson, wrote detailed letters to proprietors back in England praising the bluefish, sheepshead, and especially the red drum. He stated the red drum, “is of firm, good meat, but the head is beyond all the fish I have ever met withal for an excellent dish. We have greater numbers of these fish than any other sort. People go down and catch as many barrels full as they please with hook and line, especially every young flood when they bite. These are salted up and transported to other colonies that are bare of provisions.”

Algonquian Native Americans fishing using weirs and spears in a canoe, 1585 engraving by Theodor de Bry

1700-1800s

In 1765, a French explorer wrote detailed accounts of his fishing expeditions in the Outer Banks and along the Chowan River, which leads into the Albemarle Sound. Along his journey, he visited plantation owner, Alexander Brownrigg, who held a shad and herring fishery which today is considered the “first significant fishing operation in North Carolina” (Mark Taylor, Seiners and Tongers: North Carolina Fisheries in the Old and New South). It is believed that the methods Brownrigg employed at his fishery consisted of crews using long, hand-knit nets known as haul-seines to wrap around a school of fish while rowing rapidly in a circle surrounding them. The haul seines were then pulled back to shore using a windlass and crews would then clean, salt, and package the fish in barrels for local distribution.

The growth of fisheries along the Chowan and Albemarle Sound was then linked to the wide expansion of slavery in the confederate states from the late 18th century into the mid-19th century. North Carolina’s slave population increased from approximately 100,000 to over 330,000 between 1790 and 1860. Slaveholders and plantation owners found fish to be an inexpensive and plentiful food source for their slaves, as well as being high in protein. Fisheries began to function adjunctly to plantations, and many slaves were forced into the exhausting seasonal labor for plantation owners to yield large profits. Slaves would travel a mile or more offshore with the nets carried between two boats filled with crews of men. Mules and horses pulled the nets to shore where packing and salting sheds had been constructed along the beaches. The processing of the fish was most typically a job held by enslaved women who could process up to 6,000 fish per day. Barrels of fish were then sold and transported to markets in Baltimore, the center of the southern fish trade, and Virginia.

1800-1900s

In the years following the Civil War, North Carolina’s fishing industry grew exponentially with railroad and steamboat lines, available ice, and the consumer switch from salted to fresh seafood. Schooners from New England would travel to the Outer Banks, their ships filled with ice, in October and December to fish for bluefish and return with their catches to various northern ports. Fishermen would set up temporary bluefish camps on the beach for the short season and set up gill nets from smaller boats from which they would cast. Over 100 bluefish crews fished from Cape Henry to Cape Hatteras by the mid-1870s. White perch fisheries in the Currituck Sound began to develop after the Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal, which ran from the Currituck Sound to Norfolk, had been completed and steamboat lines ran from Elizabeth City to Norfolk, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, cutting the distribution time down from weeks to months into mere days.

Capt. George Rollingson, Fish House, Elizabeth City, NC, c. 1905, Division of Archives and History

Shad Catch, Barn Slue Camp, Dare County, N.C., c. 1905, Division of Archives and History

Individual fishermen would catch their fish along the Ocracoke Inlet to New River and would turn their hands to different species of fish depending on the season. In the early 1900s, the fishing population became so dense along the Albemarle Sound and Outer Banks that legislators passed the Vann Law in 1905 which stated that a channel or sound must remain open for the maintained passing of migrating fish.

The mullet was vital to the economic preservation of the Outer Banks and residents south of Oregon Inlet as they were so far removed from the booming fish markets and would rely upon the bartering of the mullet for simple staples such as cornmeal or other necessities. Sloops known as mullet boats would travel to small towns on the mainland where fishermen would trade their bounty for dried corn. Mullet camps were established along the Outer Banks beaches from mid-August through mid-November and fishermen would live in a crude cone-shaped huts built from timber and reeds. When the fishermen would spy ripples and shadows in the water indicating a school of mullet, they would quickly take out their boats loaded with a large gill net and surround the school of fish driving them into a circle. Fishermen would cast their nets on top of the mullet and jump into the water, splashing, to entrap the fish in the center of the net.

Outer Banks fishermen haul in a mullet seine, ca. 1884, Division of Archives and History

Commercial fishing in North Carolina began to dwindle with the rise of northern states obtaining most of their seafood from mid-Atlantic fisheries and processing facilities which were densely concentrated in the Chesapeake region. Despite the Outer Banks’ isolation and competition with mid-Atlantic markets, commercial fishing offered a livelihood to generations of both Outer Banks locals and North Carolinians in a time and place of limited opportunity. It remains an important part of the agricultural and maritime history of North Carolina. The next time you sit down for a local seafood meal in the Outer Banks, remember the generations of Native Americans, settlers, slaves, and local fishermen who trolled the bountiful waters and used the land to sustain them for hundreds of years. It is no wonder that English explorer Ralph Lane called these small barrier islands, “the goodliest soile under the cope of heaven.”

Works Cited

Powell, William S. “‘Goodliest Soile Under the Cope of Heaven.’” NCpedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/goodliest-soile-under-cope-heaven.

Taylor, Mark T. “Seiners and Tongers: North Carolina Fisheries in the Old and New South.” The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 69, no. 1, Jan. 1992, pp. 1–36.

“The Carolina Algonquian (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/articles/carolinaalgonquian.htm.